Larry Kramer — writer, advocate, “loudmouth” — helped define AIDS activism and gay life. He ruffled some feathers along the way.

In the documentary “How to Survive a Plague,” Larry Kramer silences a room full of AIDS activists with just one word. The scene takes place in 1991, a decade into the epidemic, and the members of Act Up, an organization Mr. Kramer helped found, are squabbling. “Plague!” he yells, stilling the room. He resumes, adding a few profanities that are omitted here. “We are in the middle of a plague! And you behave like this! Plague! Forty million infected people is a plague!” Mr. Kramer glowers like an Old Testament prophet. “Until we get our acts together, all of us, we are as good as dead.”

Let it be said that Mr. Kramer, now 81 and frail from illness, still does righteous fury like no one else.

He arrived in New York in 1958, after six months of compulsory military service, paying $20 a week for a big room on East 66th Street and working in the mailroom at the William Morris Agency. Since then, he has written an Oscar-nominated movie, started and feuded with two AIDS organizations, won a Tony Award and two Obies, been declared dead by a news service, called government officials idiots and murderers, compared friends to Nazi war criminals and been the first-ever recipient of the Larry Kramer Activism Award. Even people he excoriated say he helped save tens of thousands of lives. He has had his moments. When it comes to alienating people, Mr. Kramer’s closest friend once told The New Yorker, “Larry is a virtuoso with no peer.”

Now Mr. Kramer is running out of time and money, trying to finish the second volume of a novel whose 800-page first volume was widely dismissed. At an age he never expected to reach, married to a man he once skewered in print, he speaks softly and wears turquoise jewelry to ward off dangers to his health. His hearing aids emit occasional yawps of feedback.

On a spring afternoon in his cluttered Greenwich Village apartment, he was still restless, taking stock of his life. “I spend a lot of time now that I’m coming to the end, trying to look back,” he said. “Was I really happy? What are the happy memories I had? It’s often hard to come up with many of them.”

He said he only recently learned to accept that his husband could really love him. “Isn’t everyone like that?” he asked. “Do you feel loved?”

He added, “Perhaps my basic dissatisfactions are what motivate me.”

Mr. Kramer grew up outside Washington, the younger of two sons born to a Yale-educated lawyer and a Red Cross social worker. Arthur Kramer, eight years older, was the athletic son their father wanted; Larry, unhappy as a child, put on plays in his bedroom, “pretending someone was applauding me for my wonderful performance,” he said. When he swallowed an overdose of aspirin his freshman year at Yale, Arthur got Larry into therapy. “If it weren’t for my brother, I probably wouldn’t be alive today,” Larry said.

For Mr. Kramer, New York in the 1960s and ’70s was a haven of sexual revolution, which he both participated in and later criticized. He had returned to the city from London after writing the screenplay for “Women in Love,” which featured a nude wrestling scene between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed and earned him an Oscar nomination. His next screenplay was for “Lost Horizon,” which he called the worst movie ever made, but which made him rich.

“There was a lot of cruising on the streets,” he said of New York when he arrived. “That’s how people met each other. I remember the first time I went to Fire Island. I stayed in a tent. That’s all they had, big tents. You were really camping out.”

It is tempting to imagine that Mr. Kramer came into the world screaming “plague” and never stopped. But this would miss the full story, said Dr. Lawrence D. Mass, a physician and a friend of his for 50 years, through occasional estrangements and recriminations.

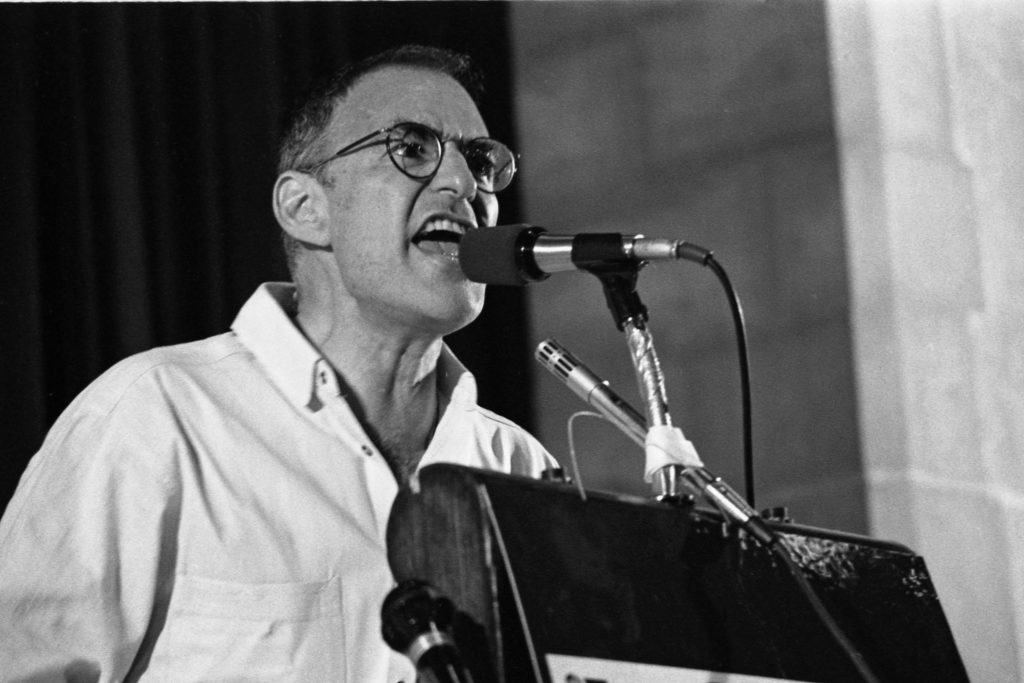

At an AIDS conference in 1987. Credit Catherine McGann/Getty Images

“You got it 50 percent right,” said Dr. Mass, who was a founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, along with Mr. Kramer and others. “He came into the world screaming, but not always ‘plague.’ That came later. But Larry was always a social critic, and a lot of that started at the level of his friends.”

He fell in love with a man named David Webster, who did not want to settle monogamously with him. In response, Mr. Kramer wrote a devastating 1978 satirical novel called “Faggots,” which depicted a demimonde of men destroying themselves in wanton pleasure. The book sold well but made Mr. Kramer a pariah.

“People were so angry and offended,” Dr. Mass said. “I don’t think there is a positive image of a gay person, not one, in the entire novel. Larry seemed to have this ridiculously outdated romantic notion of sexuality and its relationship to love, monogamy. He was this total misfit in this expanding world of gay promiscuity and the sexual revolution.”

Three years later, the emergence of a new disease made the book seem prescient, and provided a purpose for Mr. Kramer’s wrath.

“AIDS changed everything,” Mr. Kramer said.

“The first people who got sick were friends of mine,” he said. “In the Village, you couldn’t walk down the street without running into somebody who said: ‘Have you heard about so and so? He just died.’ Sometimes you could learn about three or four people just walking the dog. I started making a list of how many people I knew, and it was hundreds. People don’t comprehend that. People really were dying like flies.”

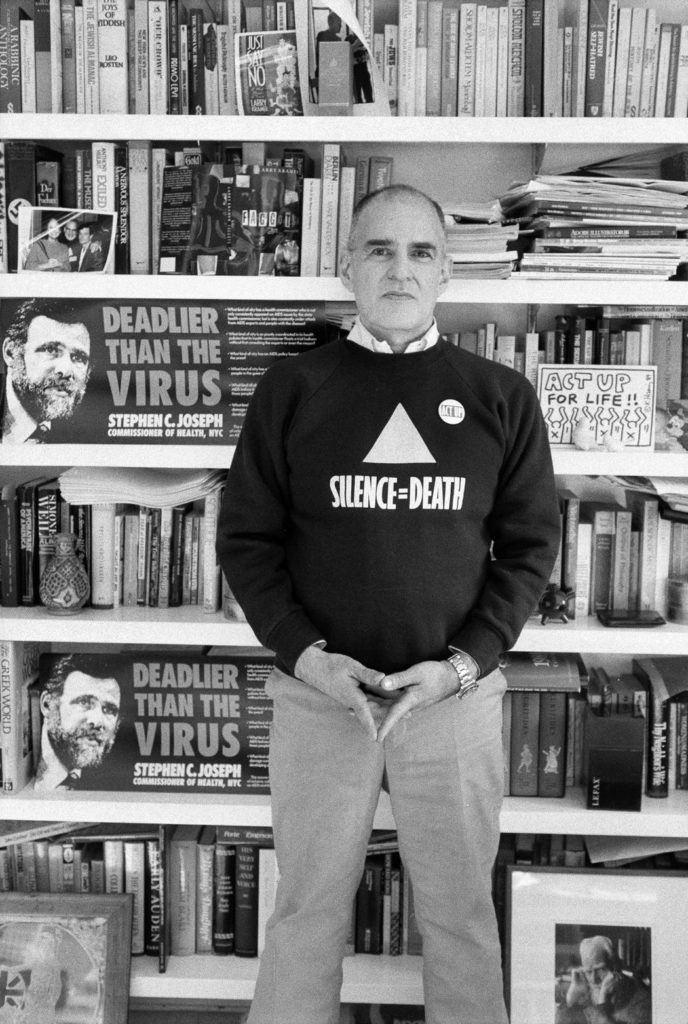

At home in 1989. The graphic on his sweater appeared on posters that activists plastered around New York City in 1987. Credit Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Mr. Kramer lashed out at peers who would not curb their sexual habits, and health care workers who would not treat people with the disease. In his Village apartment in August 1981, he convened the first meeting of what became the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the pioneering AIDS service organization. And when he fell out bitterly with the organization in 1983, he went on to start the confrontational AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or Act Up, in 1987.

“One day I was just parachuted behind enemy lines, and there was this horrific story to tell,” he said. “And that just became so all-consuming. I still don’t have any interest in anything else, except getting gay history taught in schools.”

With his earnings from movies, Mr. Kramer did not need to have a job.

“I was trying to make people united and angry,” he said. “I was known as the angriest man in the world, mainly because I discovered that anger got you further than being nice. And when we started to break through in the media, I was better TV than someone who was nice.”

He added: “So, did I think that I was going to get it? I didn’t think about it, quite frankly.”

Mr. Kramer denounced The New York Times as slow to cover AIDS; he tarred politicians, drug companies, the medical establishment and gay organizations, including members of the two he founded. He took special aim at Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, whom he compared to the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann.

A 1989 protest in front of the New York Stock Exchange organized by Act Up, a group Mr. Kramer founded, against the high cost of the HIV treatment drug AZT. Credit Tim Clary/Associated Press

“I remember the headline, ‘An Open Letter to Anthony Fauci, an Incompetent Idiot,’” Dr. Fauci said. “I said, ‘Wow, that gets my attention.’” But over time the two formed an unlikely friendship, and eventually Dr. Fauci took on a role in Mr. Kramer’s medical care.

“It’s a long and complicated relationship,” Dr. Fauci said. He remembered Mr. Kramer screaming at him on a television news show, then calling afterward to say: “‘What did you think? I thought it went really well.’ I said, ‘What can I say? Larry, I love you.’”

Dr. Fauci credits Mr. Kramer and the other activists at Act Up and Project Inform with forcing government agencies to change the way they test drugs, speeding up the process and involving patients in constructing the trials. He once said you could divide medical research into “before Larry” and “after Larry.”

“He was fearless,” Dr. Fauci said. “He scared people. He angered a lot of people. But his heart was always in the right place, and he always wanted to do things for the good of his people.”

Mr. Kramer was less effusive about their friendship.

“I’m still angry at him, as I am with the entire health care system, which starts in the White House,” he said. “There’s no question that he could have done much more, much faster — still. We had a go-round not so long ago about where is the research on the cure going.”

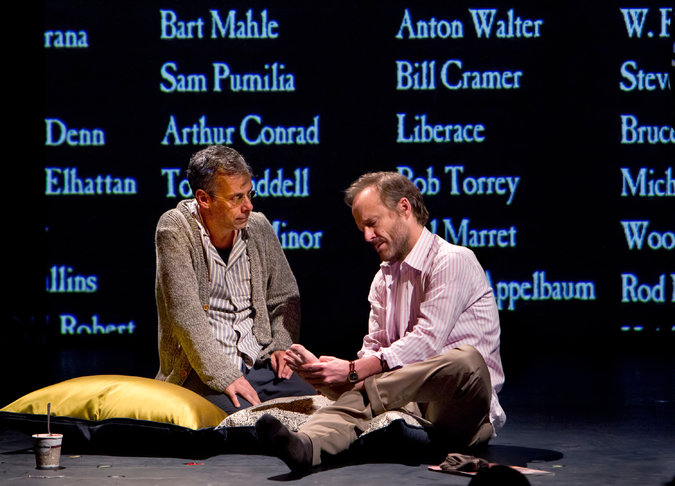

Joe Mantello, left, and John Benjamin Hickey in a 2011 production of Mr. Kramer’s play “The Normal Heart.” Credit Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Yet even amid his fiercest battles, there was another side of Mr. Kramer that came out in smaller groups, said Peter Staley, an early member of Act Up. “He was charming,” Mr. Staley said. “He was funny. It was the Jewish-mother version of Larry Kramer, where he was very interested in our lives, he was very much wanting to know who we were seeing. He loved hooking people up. He was a master matchmaker. Oh, yeah. One of my boyfriends that lasted three years was because of a Larry Kramer arrangement.”

As Mr. Kramer watched friends die in the 1980s, he declined to be tested for the virus because there were no treatments. His 1985 play, “The Normal Heart,” about the beginning of the epidemic and his battles within G.M.H.C., won accolades but further alienated some friends. (Much later, a 2011 revival on Broadway won a Tony Award.) Then, in 1988, Mr. Kramer learned that he had a life-threatening case of hepatitis B, and, in preparation for treatment, that he had H.I.V., possibly from a casual encounter in 1980, when he was trying to make Mr. Webster jealous. He never developed AIDS.

He also never got over Mr. Webster, whom he satirized brutally in “Faggots.” The two men did not speak to each other for more than a decade, and Mr. Webster once called the book “a total invasion of my life.” But in 1992, Mr. Kramer asked Mr. Webster to design a house for him in Connecticut, and their discussions rekindled the relationship. This time it blossomed as Mr. Kramer had wanted.

“He makes me very happy,” Mr. Kramer said. “I’m a pain for him, I’m sure. I can’t believe he’s with me somehow, this handsome man.”

Their life together, predictably, has not been simple. In 2001, Mr. Kramer was near death in a hospital in Pittsburgh, awaiting a liver transplant, when a wire service released a bulletin with the headline, “AIDS Activist Larry Kramer Dies.” By then he had written thousands of pages of a novel called “The American People,” a grand sweeping epic about gays in United States history.

Mr. Kramer, right, and David Webster at their wedding at NYU Langone Medical Center in 2013. Credit Courtesy of David Webster

The transplant saved his life, but he has almost died several times since the operation. In 2013, he and Mr. Webster married in an intensive care unit at NYU Langone Medical Center, where Mr. Kramer was recovering from surgery for a bowel obstruction.

“The last illness I had, I had an infection in my brain, and I was gaga,” Mr. Kramer said. “Literally almost from the day we got married it struck.” Now, he said, “I hope when I die it’s sudden and painless, so I don’t have to go back in a hospital again.”

Mr. Kramer conceived “The American People” as his crowning work, reclaiming gay history to include George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain, and tracing the history of AIDS to distant times. The cold response to the book’s first volume, released in 2015, wounded him.

“I would lie if I didn’t say yes,” he said, when asked if he had been hurt by the reviews. “It wasn’t given much serious attention. Most people seemed to review me, not the book: Loudmouth activist Larry Kramer has written a loudmouth book. I work very hard on my writing. I like to be considered a good writer.”

Stacks of manuscript pages for the second volume filled the living room. Writing it, Mr. Kramer said, has kept him alive.

Looking out onto Washington Square Park from the balcony of his apartment on Fifth Avenue. Credit Joshua Bright for The New York Times

“I hate getting old,” he said. “I hate being infirm in any way. I hate having to have caregivers come every day and give me shots. I know I’m supposed to say I’m happy I’m alive. I’m not unhappy I’m alive, but I’m not comfortable alive. Life is physically hard. The consolations are being with David and the consolations are sitting at my computer and still able to write. If I couldn’t write, I’d just as soon not be here.”

He added, “I’m determined to finish it and it’ll be on the shelves and I’ll be dead and the book will have its own life, I hope.”

The house that brought Mr. Kramer and Mr. Webster back together has been put up for sale. “We need the money,” Mr. Kramer said. His earnings from the HBO movie of “The Normal Heart” went to paying his medical bills.

“It’s been difficult to deal with,” he said. “When I first wooed David, I said, ‘I’m a rich man; you’ll be rich.’ And we’re not going to be rich, and I worry that I have enough for both of us to live to the end of our lives. That ain’t happening yet. I’m not quite sure what’s going to come of it. Some generous benefactor out there, perhaps. Everyone thinks that I was so rich because of the years of Act Up when I was.”

These days, Mr. Kramer said, the old grievances are mostly forgotten. “I don’t basically have fences to mend anymore. The people I had fights with down the line, some are dead. But even when we fought, I think we were always — I love gay people, and I think that’s the overriding thing in any relationship that I have with anyone else who’s gay. Never enough to throw them out of my life. I’ve never had huge fights with anybody. Much as I hate things about the system and this country, in terms of the people I deal with, I don’t have any.”

He laments that the collective purpose of the Act Up years dissipated as soon as effective treatments emerged in 1996. “So this great triumph — and I think what Act Up accomplished is one of the great achievements of any grass-roots organization anywhere — it had this still sad ending,” he said. “I don’t see us fighting with the fervor we’re capable of. There are still too many people that just want to party on the weekends and not think of having any responsibility.”

The sheer horror of the worst AIDS years — the die-in protests, withered bodies and rampant fear — can now be hard to conjure. While writing this article, I asked people under 40 what the name Larry Kramer meant to them. Many, including Times reporters, stared blankly or asked, “Was he the guy on ‘Seinfeld’”? They had come of age after the taming of AIDS in the developed world, and Mr. Kramer’s battles were someone else’s history.

An irony is that Mr. Kramer once owed his fame largely to his failures: Had AIDS been stopped when he first sounded the alarm, few would remember him. Now his fame is diminishing because of his successes.

He carried on regardless, holding on to the role that made him most vital: warning that gay men are living in a plague, that complacency and government negligence have enabled the plague to continue, that sexual promiscuity is an invitation for the next deadly virus, that homophobia has not gone away.

“I don’t think that things are better generally,” he said. “We have people running this government who hate us, and have said they hate us. The fight’s never over.” In his quiet way, Larry Kramer is still yelling.

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ  поиск по ресурсному центру

поиск по ресурсному центру