Reducing the size of the HIV reservoir is viewed as an essential step in achieving a cure for HIV infection

ABX464, a new drug that stimulates the clearance of HIV from infected cells, reduces the reservoir of HIV DNA in the body but does not delay the rebound in viral load when antiretroviral treatment is interrupted, Linos Vandekerckhove of the University of Ghent reported at the 16th European AIDS Conference (EACS 2017) on Thursday in Milan.

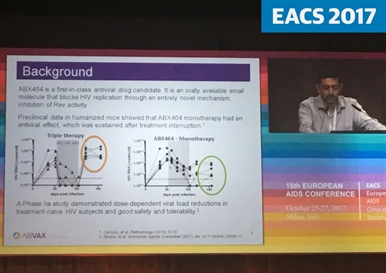

Linos Vandekerckhove presenting at EACS 2017. Photo by BHIVA.

Reducing the size of the HIV reservoir is viewed as an essential step in achieving a cure for HIV infection. HIV integrates into immune system cells in the body where it lies dormant until the cell is activated. At this point, HIV DNA in the cell begins the process of replication that leads to the production of new HIV virions that will be released from the cell, going on to infect other cells.

A very small amount of HIV is released from these cells each day in people taking antiretroviral therapy, but is immediately cleared by antiretroviral therapy.

When treatment stops viral load rebounds quickly, often rising to pre-treatment levels within a few weeks.

What’s unclear is whether reducing the HIV reservoir might slow down this process. Several people who stopped treatment after HIV became undetectable have gone for prolonged periods without viral rebound. But, despite the use of highly sensitive tests which could not detect HIV DNA or measured it at very low levels, sufficient viral DNA remained in these individuals to spark eventual viral rebound months after stopping treatment.

Despite these findings, HIV cure researchers maintain the hope that shrinking the reservoir might enable the immune system to control HIV without eliminating the virus entirely, and without the need for lifelong antiretroviral therapy, a so-called functional cure.

To date, studies looking at reduction of the HIV reservoir have observed modest reductions in HIV DNA in cells after prolonged antiretroviral therapy. The most substantial increases have been observed in children and adults who started treatment within days or weeks of infection before HIV infection became extensive in the body.

Other studies have looked at the impact of agents designed to activate HIV-infected cells and clear HIV DNA from those cells, but have found only modest effects, and at the risk of considerable toxicity.

Finding other agents that might reduce the number of HIV-infected cells more profoundly, without unacceptable toxicity, is essential for exploring the possibility of a functional cure for HIV infection.

ABX464 is a new agent developed by the French pharmaceutical company Abivax.

ABX464 stops HIV replication by interfering with the activity of Rev, an HIV protein essential for making complete strands of HIV RNA. When exposed to ABX464, HIV produces short fragments of RNA that cannot be used to produce new viruses. Instead, when HIV is replicating within cells, these fragments produce small peptides which migrate to the cell surface. Once they arrive at the cell surface, these HIV peptides alert the immune system to the presence of HIV-infected immune cells. An immune response can then eliminate these HIV-infected cells.

In theory, ABX464 should reduce the number of HIV-infected cells that form the reservoir of HIV in the body. The effectiveness of the drug can be assessed by measuring levels of cellular HIV DNA.

ABX464 has been shown to reduce HIV viral load in previously untreated people in a dose-ranging study presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in 2016. Four out of six people who received the highest dose (150mg once daily) experienced a viral load reduction of more than 0.5 log10 copies.

Linos Vandekerckhove of the University of Ghent reported results of a phase IIa randomised trial of ABX464 or placebo.

The study recruited 30 people with HIV who had been receiving treatment with boosted darunavir monotherapy for at least eight weeks prior to joining the study, and who had viral load below 50 copies/ml. Participants had been taking antiretroviral treatment for a median of 5.6 years before entering the study. Study participants were predominantly male and white.

The participants were randomised to add ABX464, dosed once daily at 50mg or 150mg, to their existing regimen or to receive a placebo. The study was double-blind. After 28 days all participants interrupted treatment and resumed treatment if their viral load rose above 1000 copies/ml.

The study evaluated levels of integrated cellular DNA and total cellular HIV DNA at days 0 and 28, and the time to viral load rebound after treatment interruption.

Eight study participants received an ABX464 dose of 50mg before a protocol revision increased the daily dose to 150mg.

Twenty-six participants completed the 28-day treatment interruption. Two out of eight in the placebo arm and two out of 20 in the ABX464 arm discontinued treatment. Discontinuations in the ABX464 arm were due to premature viral rebound and adverse events.

After 28 days off treatment, eight of the ABX464 arm were classified as responders (53%), having an HIV DNA reduction greater than 25% (mean change -186 DNA copies/million peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs], compared to none of the placebo group). The mean reduction in total HIV DNA in responders was 38%.

Baseline HIV DNA levels were below 50 copies per million PBMCs in five of the ABX464 group and two of the placebo group and they were excluded from the responder analysis.

HIV DNA levels rose by a mean of 67 DNA copies/million PBMCs in seven participants in the ABX464 arm (non-responders).

The mean baseline total HIV DNA in responders and non-responders was not specified but baseline HIV DNA ranged from 146 copies/million PBMCs to 961 copies/million PBMCs and no correlation was apparent between the level of baseline HIV DNA and the magnitude of reduction, although, again, this change was not specified in the results presented.

Reductions of greater than 25% in integrated HIV DNA (HIV DNA most likely to lead to HIV replication) were observed in seven of 17 in the ABX464 arm (a mean of -131 copies/million PBMCs) and two of the placebo arm (-41 copies/million PBMCs). The mean reduction in responders was 55%.

Despite these reductions in HIV DNA there was no delay in HIV viral rebound in the ABX464 arm after treatment interruption compared to the placebo group, indicating that the degree of HIV DNA reduction was insufficient to affect the speed at which viral replication re-emerged after the interruption of treatment.

The most common adverse events were mild-to-moderate abdominal pain and headache (grade 1 or 2) and one person discontinued study drug owing to abdominal pain.

Follow-up studies will look at a longer period of ABX464 treatment (84 days) and at the time needed to achieve maximal reduction of the HIV reservoir in recently infected and chronically infected people with well-suppressed viral load.

However, responding to questions after his presentation, Linos Vandekerckhove questioned whether further treatment interruption studies would provide useful information without more potent drugs for clearing HIV DNA. “Much more profound decreases in HIV DNA are needed – as a general strategy I would not recommend it,” he said.

Related News

Taking large numbers of non-ART drugs associated with increased risk of hospitalisation and death for HIV-positive people

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ  поиск по ресурсному центру

поиск по ресурсному центру