Therapies to prevent infection are advancing in a crowded field.

Several vaccines and drugs for preventing the spread of HIV are showing signs of success in clinical trials, three decades after scientists began the search. But some researchers fear that progress will stall without a coordinated strategy to ensure that the most promising therapies to prevent infection win support from policymakers and reach the people who need them.

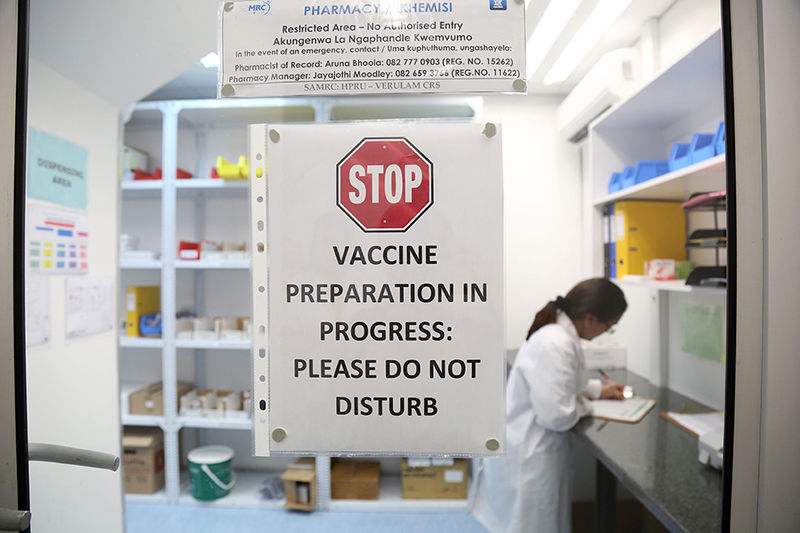

Researchers around the world are conducting 12 late-stage trials of HIV vaccines. Credit: Jackie Clausen/The Times/Gallo/Getty

A meeting convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland, on 28 February to 1 March aims to address a lack of long-term thinking about the factors — such as cost and ease of use — that can determine whether a vaccine or other preventive therapy succeeds in reducing disease. Some HIV researchers argue that they should study these issues now, while clinical trials of potential vaccines and drugs to block HIV infection are ongoing, to avoid delays in delivering effective therapies to people at risk of infection. Many hope that the WHO meeting will trigger broader discussions about how to support such research given limited resources, and how to prioritize therapies in development.

Waiting to conduct such studies after trials are finished prolongs the time until a preventive therapy reaches people, and in the meantime, the epidemic grows. Worldwide, about 1.8 million people contracted the disease in 2016. “You need to have a good idea about where you want to end up and all of the steps you need to make to get there,” says Mark Feinberg, president of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative in New York City.

But it is not clear who would make decisions about which projects to prioritize, or when such choices would be made.

Some 25,000 people around the world are participating in clinical trials of treatments to prevent HIV infection. Twelve late-stage trials worldwide are testing experimental vaccines; these include a 2,600-person study in southern Africa of a vaccine designed to block multiple strains of the virus. Others are assessing the potential of proteins called broadly neutralizing antibodies, which might stop HIV from infecting a person’s immune cells. And a pair of phase III trials has enrolled 7,700 people to test whether injections of a drug called cabotegravir can prevent HIV infection for two months at a time.

Delivery concerns

At the meeting, researchers, policymakers and HIV activists will discuss stumbling blocks that have limited the use of potent vaccines and treatments against other diseases, such as high costs and cumbersome delivery requirements. Because no therapy has approached 100% protection against HIV, regulators face tough decisions when considering the cost and effort of delivering treatment to people at risk. In 2009, for example, a phase III study1 of the most promising vaccine identified so far found that it reduced a person’s risk of contracting HIV by only one-third. Health authorities did not recommend it for widespread use.

A modified version of that vaccine is now being tested in 5,400 people in South Africa, and researchers hope that it will reduce a person’s chance of contracting HIV by at least 50%. But even if the trial succeeds, the expense and difficulty of administering the vaccine, which must be given as six shots over 18 months, could make it a hard sell to policymakers and funders. Health-care workers around the world struggle to persuade healthy people to get one-time shots that are highly effective against other deadly diseases.

Similar concerns surround the antibodies in development, because they are given as intravenous infusions, and it is unclear how long treatment must continue to prevent HIV. The antibodies are also relatively expensive to make. Eventually, scientists must be prepared to choose which projects to stall, and which to supplement with studies aimed at developing cheaper, easier ways of administering a given therapy, says Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, an HIV-prevention advocacy organization in New York City.

Money is limited, as is the pool of people available for clinical trials, which becomes larger and more complex as a vaccine or antibody treatment progresses towards the market. “We will need prioritization,” Warren says. “That view needs to be driven by science and financial realities, and the decision process needs to be clear and transparent.”

Another issue facing researchers is how to improve the likelihood that people at risk of HIV infection will take preventive treatments. Success is not guaranteed: Truvada, a daily pill for preventing HIV infection, has not reduced the number of new HIV cases globally since regulators approved it six years ago. In eastern and southern Africa, for instance, young women rarely take the drug, even though they account for 26% of the region’s new infections. Tian Johnson, founder of the African Alliance for HIV Prevention in Johannesburg, South Africa, says that researchers did not adequately consider how poverty, pregnancy, discrimination and abuse might affect whether young women at risk are likely to seek out Truvada. “If you disregard the complexity of a woman’s daily life and reality, you put at risk the millions of dollars you invest in developing a product,” he says.

Despite the challenges ahead, the fact that such discussions are happening is an important step forward, says Feinberg. “You can’t keep your head in the sand,” he says. “You need to work ahead and think of ways that we as a research development community can solve these problems — and they are solvable.”

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ  поиск по ресурсному центру

поиск по ресурсному центру