Former Soviet countries in the Eastern European and Central Asian (EECA) region are fighting the prevailing perception that their outdated hospital-based tuberculosis (TB) programs are failing to provide patient-centered care. Since 2005, Georgia has emerged as the regional leader in decentralizing TB services and implementing country-wide directly-observed treatment (DOTS) coverage in line with the major components of the international Stop TB strategy.

Through several waves of healthcare reforms, former stand-alone TB dispensaries across the country, except the major cities, have become physically integrated into Primary Health Care (PHC) centers which are now owned by private providers who contract TB doctors (in Georgia—only phtysiatrists) and DOT nurses to deliver TB services as part of the TB state program. Universal access to diagnostic and treatment services is ensured and facilitated by demand-side incentives and robust monitoring and evaluation practices which are reflected in high 83%treatment success rate for all new and ralapse cases registered in 2014.

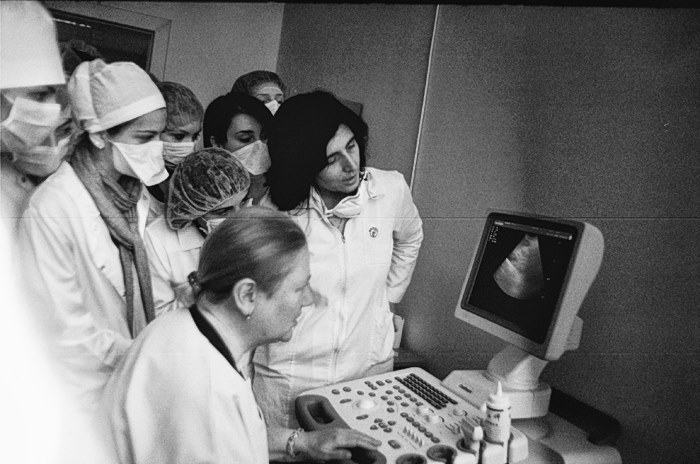

Photo credit: Sophio Gokhelashvili

However, the most challenging drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) remains Georgia’s Achilles heel, as no more than 43% of patients completed treatment successfully in 2013, and every third of them interrupted treatment in the past three years.

The latest TB adherence report in Georgia found that almost half of drug-resistant patients are lost to follow-up already by the 8th month of treatment. This figure is not surprising if we put ourselves in the shoes of patients who have to travel to TB units six days a week for at least 18 months (DOTS units are not within walking distance for most patients, and flexible programs like Video-Observed Treatment (VOT) have limited coverage under pilot schemes). Poor management of side effects from anti-TB drugs also contributes to dropouts. Ironically, hospitalized patients in the Tbilisi TB center are better off as they have access to medical specialists who manage their adverse reactions. In rural areas, patients do not always use general healthcare services, required to complement their TB treatment. Despite structural integration of TB services into primary care facilities, the vertical TB program is not linked with the PHC services. As a result, TB patients are not well informed about certain free general care services under the UHC program, and they avoid additional expenses associated with seeking specialists on their own. Grossly underpaid, TB doctors are discouraged to meticulously engage in holistic patient care which are required to support drug-resistant patients. Budding medical students see no appealing career path in phthisiatry either, so the numbers of TB specialists are declining. The shortage is already felt in some regions where only one TB doctor serves several districts. Lack of coordination between the TB program and primary care services exacerbates sub-optimal organization of TB services. While a TB doctor, family doctor and other specialists often occupy the same facility, they do not share patient records and rarely cross-manage co-morbidities. As a result, formal decentralization of TB services in rural and semi-urban areas falls short of providing country-wide patient-centered care: if you want to receive quality treatment, better go to the Tbilisi TB center. Although the government is committed to addressing these shortcomings,

it is unclear whether a vertical program can cope with these challenges, even with further investments.

Drug-resistant patients require a flexible chronic care model which is more appropriate for the primary care level. Moreover, the declining TB epidemic will eventually phtysiatry redundant and the costly TB center unsustainable. This raises the question: how to uphold the benefits of holistic care offered at the primary care level without losing the capacity of a strong infection control vertical program? How much responsibility for TB care can family doctors successfully assume? Georgia has decided to test the feasibility of integrating TB services into primary care. Currently, I am here studying how such model could work.

I conducted a literature review on TB case management at the primary health care (PHC) level and found that

integration of specialized TB services into general practice is now understood to be essential to patient-centered care.

Conceptually, PHC centers which are operated by a family doctor or general practitioner can be ideal sites for participating in TB control as they are geographically close to patients, can deal with a broad range of health conditions, and ensure confidentiality which is crucial for stigmatized TB patients. However, it does not mean that all family doctors are expected to fully treat TB and assume all responsibilities of TB specialists. A quite successful model of TB care features multidisciplinary team case-manegement, practiced in countries like Norway, UK, and the US, which have 50% fewer patients lost to follow up, than Georgia (data on Norway, UK, USA). Particularly designed to support patients with more complex needs, multidisciplinary teams include a mix of prefossionals such as a TB lead physician (general practitioner), case manager, infectious disesase doctor or other TB specialist, as well as a social worker, peer supporter, psychiatrist, and legal services representative. However, all countries have different history of TB epidemic and TB care management, making it impossible to simply adopt more successful models. Reforming vertical TB programs is still new, so countries learn by trial and error. Several countries in the EECA region started engaging family doctors in TB control beyond case identification and diagnostic referral, enabling them to provide DOTS in Uzbekistan, Romania and Moldova, and even allowing family doctors in Serbia to prescribe anti-TB drugs. Unfortunately, there is little documented evidence from international practices in shifting TB service provision from specialized care to general practice. Country reports and project evaluations usually discuss normative dimenstions of interventions, and document specific inputs and outcomes, but rarely go in depth on the rationale behind certain programmatic choices and on-going operational challenges.

We need more present-day evidence that fills the gaps of publication delays to inform policy decisions promptly.

In March, Georgia launched a 48-month Results-Based Financing (RBF) scheme for tuberculosis care, hoping to incentivize family doctors and TB specialists (phtysiatrists and DOT nurses) to collaborate in patient-centered TB management. It is expected that giving family doctors more responsibility for TB case management would bring health services closer to patients. Engagement of family doctors would also stimulate the creation of linkages between TB doctors and other health specialists, ensuring that patients receive quality health services along the continuum of care. This program is currently in the design stage. Selective RBF schemes for TB have been introduced in Kazakhstan and Moldova, and pilots are underway in Armenia and Romania. Little impact evidence is documented in this area as well, and I hope the blog will encourage more timely and informal international knowledge exchange.

What we understand so far is that countries have to deal with a number of health system and individual barriers related to health financing, medical beliefs and attitudes, as well as communication and leadership skills of healthcare managers at all levels of care. Several studies consistently note that proper coordination of TB case management activities did not happen when family doctors and TB specialists were assigned new roles without ensuring that they understand and accept them. Other studies warn us not to underestimate the importance of healthcare managers whose leadership and motivation are as crucial as the competency of medical specialists. Moreover, designing a flawless intervention from a system’s perspective will not ensure acceptability and uptake of the innovation by health professionals and patients.

Studies in Brazil, Turkey and India note that health workers’ resistance to changing professional practice was one of the major impediments to smooth TB integration in general practice. Hierarchical professional relationships among medical specialists are common in vertical programs such as here in Georgia. To establish successful case management of TB in primary care, healthcare managers are faced with the challenging task of ensuring that family doctors do not feel dominated and undervalued by TB specialists and, on the other hand, they do not underestimate their capacity to take new responsibilities and make a positive change for TB patients. The bottom line question is:

HOW to ensure harmonious task shifting when it requires not only acquisition of new skills and competencies but ultimately a paradigm shift for healthcare workers and patients?

Lessons from other countries suggest that functional information sharing systems and strong linkages between healthcare professionals at all levels of care become crucial to successful integration. Delayed or incomplete patient records disempower healthcare providers as they experience inefficiency of the system, caused by duplication of activities and endless paperwork. But again, HOW to establish these linkages? What crucial inputs should not be overlooked, especially once financial and regulatory mechanisms are aligned with the intended model of care? How to establish clear guidelines for the members of TB care team, while accommodating individual patient needs and variations in health resources across the country? How to ensure personal accountability while rewarding team performance?

Even though a lot of unanswered questions remain, the momentum for sustainable transformation is there, giving us an excellent opportunity to exchange the newest evidence and accelerate global progress towards TB eradication. As we will be following how Georgia deals with these challenges, we encourage you to share with us your experiences integrating TB services in the primary care, including innovative solutions and treatment models that promote patient-centered care.

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ

ПОИСК ПО САЙТУ  поиск по ресурсному центру

поиск по ресурсному центру